From the macroeconomic point of view, the most important fact

about the Chinese economy is its extraordinary savings. In 2010, gross national

savings reached 50 per cent of gross domestic product. Since then, it has

fallen a little. But it was still 44 per cent of GDP in 2019. While household

savings are extremely high, averaging 38 per cent of disposable incomes between

2010 and 2019, they account for slightly less than half of all these savings.

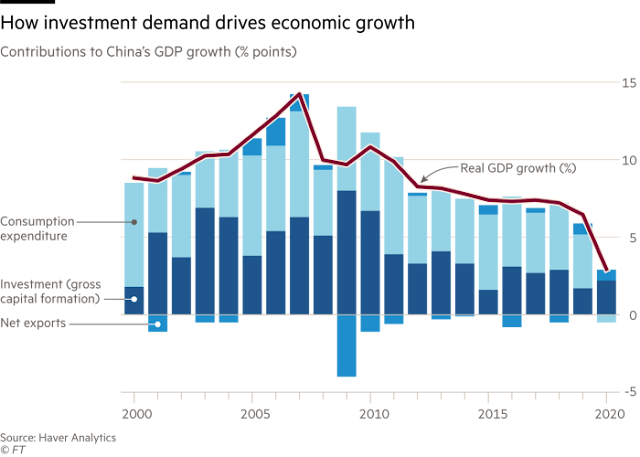

The rest consist mainly of corporate retained earnings. Investment plus net

exports have to match savings when the economy is operating close to potential

output, if it is not to fall into a slump. Since the global financial crisis, net exports have been a small share of

GDP: the world would not accept any more. Total fixed investment duly

averaged about 43 per cent of GDP from 2010 to 2019. Surprisingly, this was 5

percentage points higher than between 2000 and 2010. Meanwhile, growth fell

significantly. This combination of higher investment with lower growth indicates a

big fall in the returns on investment

Yet there are even bigger problems than

this suggests. One is that the high investment is

associated with huge increases in debt, especially of households and the

non-financial corporate sector: the former jumped from 26 to 61 % of GDP

between the first quarters of 2010 and 2021 and the latter from 118 to 159 %.

Another is that a substantial part of this investment has been wasted. Xi

Jinping himself has spoken of the need to shift “to pursuing genuine rather than

inflated GDP growth”. This has to be a big part of what he meant. This

combination of high and unproductive investment with soaring debt is closely

related to the size and rapid growth of the property sector. A 2020 paper by

Kenneth Rogoff and Yuanchen Yang argues that china's property sector contributed 29 % of GDP in 2016. Among high-income economies,

only pre-2009 Spain matched this level. Moreover, almost 80 percent of this

impact came from investment, while about a third of China’s exceptionally high

investment has been in property

A number of powerful indicators show that this investment is driven by unsustainable prices and excessive leverage, and is also creating huge excess capacity: the price to income ratios in Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen are far higher than in other big cities around the world; housing wealth accounted for 78 per cent of all Chinese assets in 2017, against 35 per cent in the US; household debt ratios are comparable with those in high-income countries; vacancy rates and other measures of excess capacity are high; and rates of home ownership had reached 93 per cent in 2017. Furthermore, family formation is slowing, China’s population is aging and 60 % of it is already urbanised. All these signal that the property boom must end.

Since the

government controls the Chinese financial system, it can prevent a financial

crisis. A large fall in house prices and a big negative

impact on household wealth and spending are likely, but might be

avoided. The likeliest threat is that investment in

property will collapse. This would have a large negative effect on local

government finances. But, above all, it would leave a huge hole in

demand. Rogoff and Yang argue that “a 20 % fall in real estate activity could

lead to a 5-10 per cent fall in GDP, even without amplification from a banking

crisis, or accounting for the importance of real estate as collateral.” It

could be worse.

Between 2012 and 2019,

investment contributed 40% of China’s growth in demand. If investment in

property fell sharply, it would leave a huge shortfall. Yet tolerating this

painful adjustment would ultimately be desirable.

It should improve the welfare of the population: after all, building unneeded

properties is a waste of resources. Slowing the

recent pace of property investment would also be a natural consequence of the

“three red lines” for property developers imposed by the state last year: hard

limits on a company’s debt-to-asset ratio, its debt-to-equity ratio and its

cash-to-short-term-debt ratio. The main policy

now should be to shift spending towards consumption, and away from the most

wasteful investment. This would require redistribution of income towards

households, especially poorer households, as well as a rise in public

consumption. Such a shift would also fit with the recent attack on

the privileges of great wealth. It would also require big reforms, notably in

taxation and the structure of public spending. In addition, investors should be

shifted away from property toward the transition away from high carbon

emissions. That too would require big policy changes.

Crises are also opportunities. The Chinese government is well aware that the great investment boom in property has gone far beyond reasonable limits. The economy needs different drivers of demand. Since the country is still relatively poor, a prolonged economic slowdown, such as Japan’s, is unnecessary, especially when one considers the room for improved quality of growth. But the model based on wasteful investment has reached its end. It must be replaced

沒有留言:

張貼留言